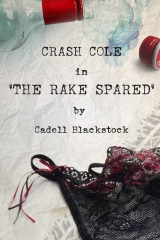

Cadell Blackstock, author of Crash Cole in ‘The Rake Spared’, itself an adaptation of the Don Juan story, reflects on Patrick Marber’s latest production of his own play, starring David Tennant as the eponymous DJ.

Even Patrick Marber would admit that reviews of the new production of Don Juan in Soho, his contemporary adaptation of Moliere’s Dom Juan currently running in London’s West End, have been mixed. Reading them before I went to a performance last night, I was surprised by just how divided critics have been. It’s an energetic, well-staged production and Tennant is – to my mind – rakish in disposition as well as character, inhabiting the small stage with flawless poise and a beautiful control of his own physical space. But I left the theatre wondering if the critical reception had more to do with the problem that a contemporary adaptation of this particular morality tale creates, than any flaws in the production.

Even Patrick Marber would admit that reviews of the new production of Don Juan in Soho, his contemporary adaptation of Moliere’s Dom Juan currently running in London’s West End, have been mixed. Reading them before I went to a performance last night, I was surprised by just how divided critics have been. It’s an energetic, well-staged production and Tennant is – to my mind – rakish in disposition as well as character, inhabiting the small stage with flawless poise and a beautiful control of his own physical space. But I left the theatre wondering if the critical reception had more to do with the problem that a contemporary adaptation of this particular morality tale creates, than any flaws in the production.

Marber has updated the play since its first performances in 2006, infusing some clever references to the current US President as well as more diverse cultural benchmarks. But what really stood out for me was DJ’s gorgeous late soliloquy where he lambasts and belittles the contemporary obsession with parading our lives in public for all to see. ‘Whatever happened to privacy?’ he demands before excoriating our desire to share every last fragment of all that should be kept to ourselves. It’s a theme I explore in Crash (though it was written before social media really exploded) through Crash’s sudden ability to hear the thoughts of everyone around him. As a celebrity, Crash has lost his own privacy, but he is the same willing conspirator in that as we are in our own loss of privacy now. He did it to himself and he has to pay the price for that. As beer brand Bud Light puts it in its current poster campaign, ‘The internet never forgets’.

But watching the play last night, I wondered whether Marber’s problem now is one that didn’t exist 11 years ago: that the world has become so chaotic and we have been exposed to so much awfulness, transgression and disdain for decency and truth, that our ability to be shocked has diminished exponentially, almost to nothing. Marber has written comically, to be sure, to save this from being a miserably dark tale of self-destruction, but when you really get down to it, absolutely nothing DJ does is remotely shocking. He does not transgress. We accept his behaviour in the context of what is common now: everyone’s right to do as they please. So what saves a modern adaptation of Don Juan from being nothing more than fluent comedy?

I asked myself that same question when I wrote Crash. Though I borrowed more from Mozart’s Don Giovanni than Moliere, I chose to tell the story of his decline indirectly by considering whether he has any relationship whatsoever with his own conscience. There is a point at the end of Don Giovanni as he faces up to the statue of the Commendatore where you sense a filament of doubt in Giovanni’s mind: has it all been worth it? It would depend on the ‘it’, of course. What sort of ‘it’ might genuinely cause him to wonder? And what sort of ‘it’ would still be shocking enough to our contemporary state of mind?

I asked myself that same question when I wrote Crash. Though I borrowed more from Mozart’s Don Giovanni than Moliere, I chose to tell the story of his decline indirectly by considering whether he has any relationship whatsoever with his own conscience. There is a point at the end of Don Giovanni as he faces up to the statue of the Commendatore where you sense a filament of doubt in Giovanni’s mind: has it all been worth it? It would depend on the ‘it’, of course. What sort of ‘it’ might genuinely cause him to wonder? And what sort of ‘it’ would still be shocking enough to our contemporary state of mind?

Conscience is a difficult thing to explore, especially through the eyes of someone who doesn’t apparently have one. In the opera, the moment of uncertainty is so fleeting you might not notice it were the music not so deeply unsettling in itself. And it wouldn’t be a retelling of Don Juan if he had regrets from the outset. His flagrant disregard is part of what makes him so compelling, so charming. So I decided to explore where the tipping point is of understanding the terminal impact of his own actions. And one of the best ways to do that in the context of the original story was to approach it from the other side of the moment when it would matter: his death.

When Crash wakes up at the start of the novel from an almost fatal incident, he has physically passed the tipping point, but he can’t remember what it is. Suspended virtually at the point of his own death, and hostage to those who have kept him alive, he must retrace his steps through his filthy disregard for others to find out what he did, and why someone has tried to kill him over it.

Marber’s DJ ultimately doesn’t care. He is living the life he most wants to lead. ‘At least my lies are honest,’ he claims at the start of that soliloquy. He cannot shock himself. But for me – and perhaps for the critics of Marber’s current production – the absence of genuinely shocking behaviour for anyone, particularly Elvira’s brother Aloysius, creates a narrative dilemma. DJ is simply being as self-indulgent as the rest of us when we tweet our every thought. He is not shocking us, not any more, because in 11 years since this play was last produced, life has become so appallingly predictable in all its awfulness.

It will remain to be seen whether my choice of shocking behaviour for Crash will last the test of time or not. But there’s so much more to Don Juan than how finely he treads the line between right and wrong, or how that line moves. It’s how his voice – and that of the statue – echoes in us.

****

You can find out more about Crash here on the allonymbooks blog, you can read about the similarities between Don Giovanni and How I Met Your Mother here, or you can download the book at Amazon.